There is a good chance that you use systems using the Raft algorithm, or a modified version of it, every day. It’s the engine for consensus in systems like etcd (the backbone of Kubernetes), Kafka (with KRaft), Redis (with RedisRaft), Consul, and many other distributed databases and services.

In this series, we’ll demystify Raft by implementing a simplified version of it in Ruby. In this first post, we’ll tackle the “why” and “how” of consensus and cover two major problems Raft solves: electing a leader and replicating logs.

What is consensus, and why is it so hard?

In a distributed system, you have multiple servers (we’ll call them nodes) that need to work together and agree on the state of the world. This “state” could be a piece of configuration, a user’s data, or the order of operations.

The process of getting all nodes to agree on a single value or sequence of values is called consensus.

Looks simple, right? Well, it is not. In distributed systems, you have to handle challenges like unreliable networks where messages might get lost, or nodes that can crash or become unresponsive. The real complexity lies in ensuring the system state remains correct and consistent—even when things go wrong, which they inevitably will.

This is the problem consensus algorithms solve. They provide a formal, proven set of rules for nodes to follow to maintain a consistent, shared state. While there are several famous algorithms like Paxos and Zab (developed by ZooKeeper), we’re focusing on Raft because it was designed with a specific goal in mind: being easy to understand and implement.

Enter Raft: A consensus algorithm designed for humans

Raft breaks down the complex problem of consensus into three major parts:

- Leader election: How do nodes agree on a single node to coordinate the system?

- Log replication: How does the leader ensure that all other nodes have an identical copy of the state changes?

- Safety: How do we guarantee the system remains correct, especially when failures occur?

The building blocks of Raft

Node states: Who’s who in the cluster

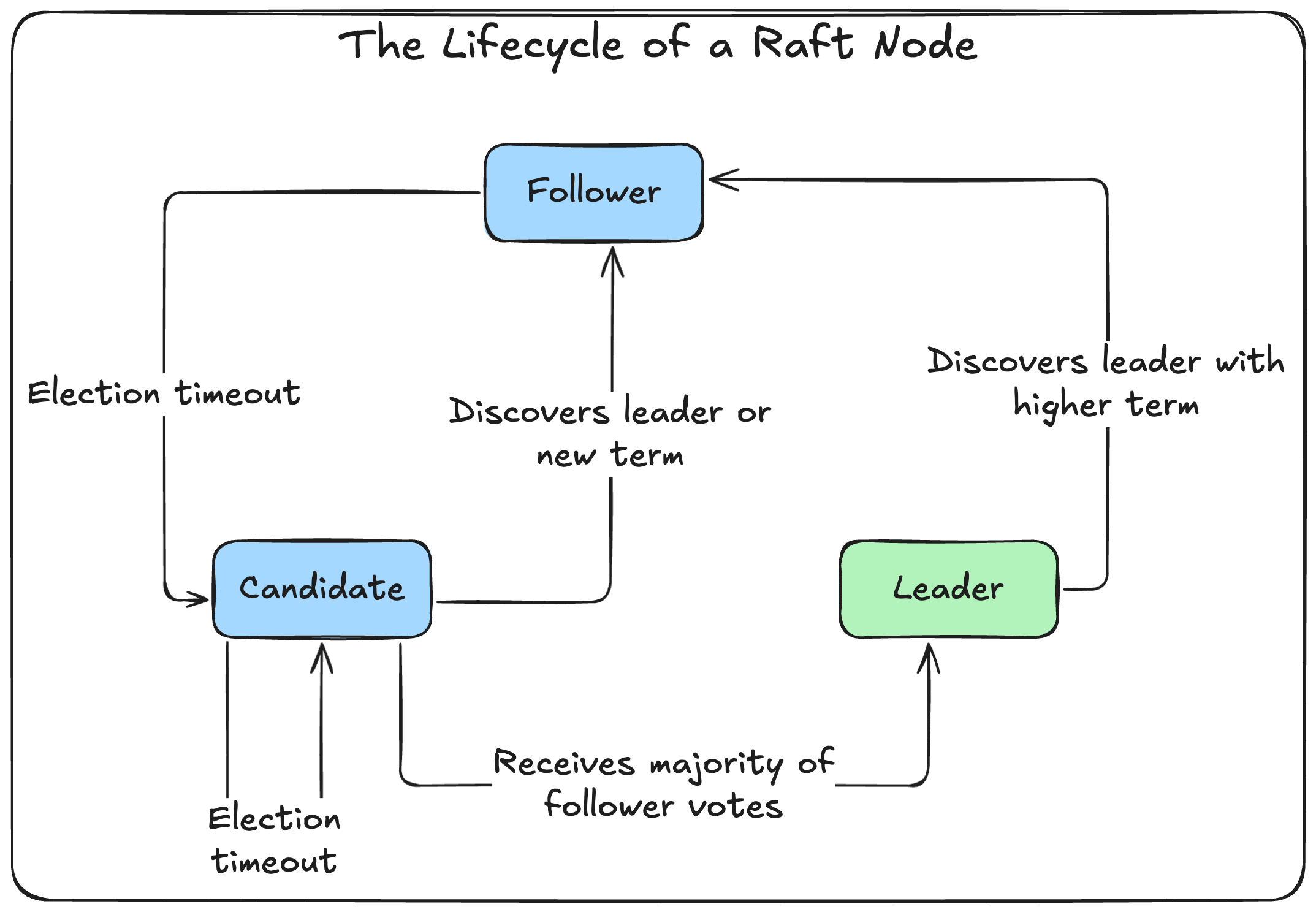

A node’s life is a continuous transition between the following states:

- Follower: The default state. Followers are passive; they simply respond to requests from the Leader and Candidates.

- Candidate: A node that is actively trying to become the new Leader.

- Leader: The single node responsible for managing the cluster, handling all client requests, and replicating state changes to the Followers.

Terms: Raft’s logical clock

Raft uses a term number as a logical clock to keep things in order. A term is an arbitrary period of time, and each term begins with a leader election.

If an election is successful, a single leader manages the cluster for the rest of the term. If an election fails (a “split vote”), the term ends, and a new term (with a new election) begins.

Log: The record of state changes

Raft’s log is a sequence of entries, each containing a state change. The log is used to store the state of the system and to replicate it to the followers.

The log is also used to ensure the system state remains consistent, even when failures occur.

Leader election: The heart of Raft

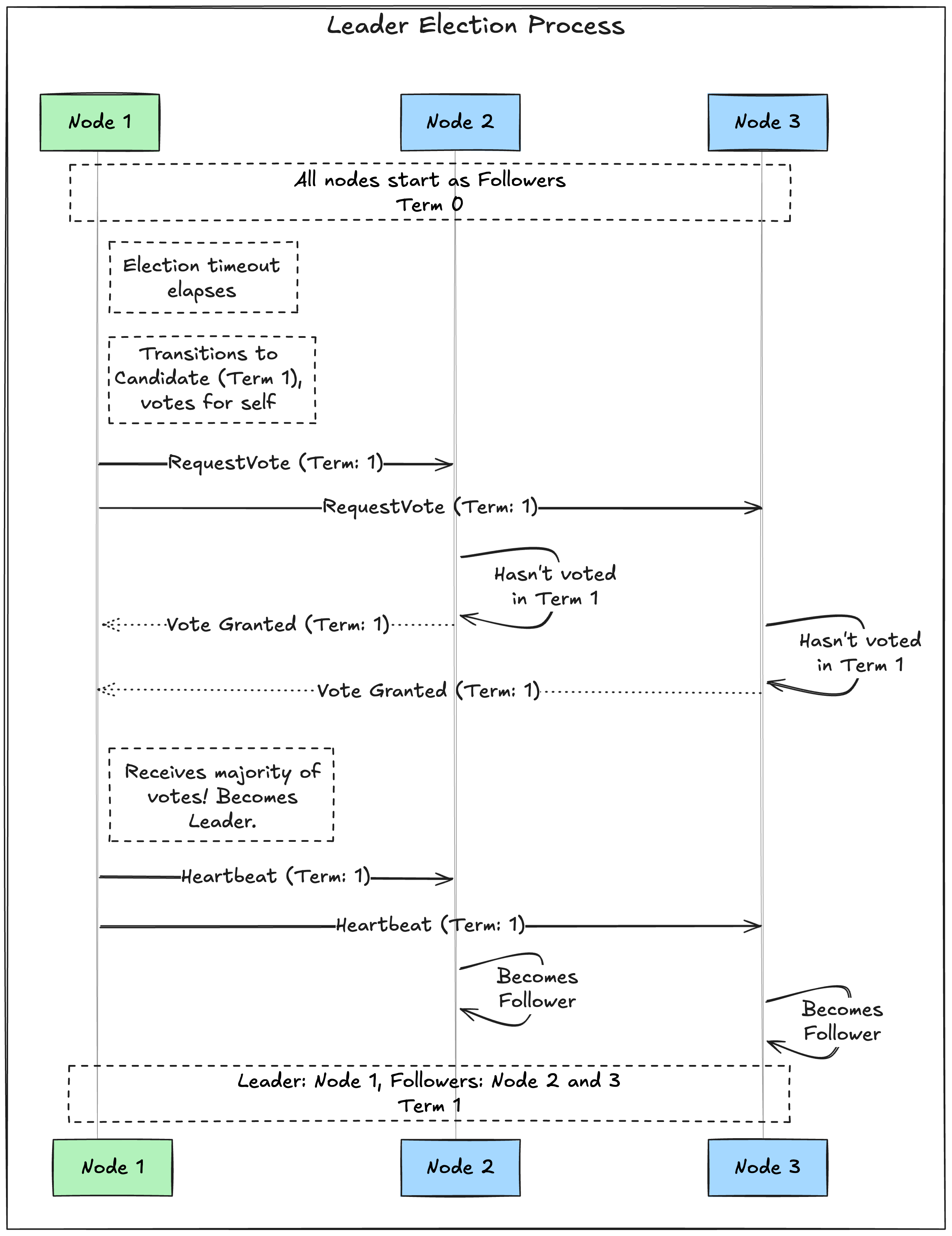

When a cluster first starts, all nodes are Followers in term 0. If a follower doesn’t hear from a leader for a certain amount of time (the election timeout), it assumes the leader has failed and triggers a new election.

Here’s how that works:

- Become a candidate: The follower increments the current term (e.g., from

0to1), transitions to the Candidate state, and votes for itself. - Request votes: It then sends a

RequestVotemessage to all other nodes in the cluster, asking them to vote for it in the new term. - Voting: When a follower receives a

RequestVotemessage, it will vote for the candidate if and only if:- It hasn’t already voted in the current term.

- The candidate’s log is at least as up-to-date as its own (we’ll dive deep into this safety rule later in this series).

- Winning the election: If the candidate receives votes from a majority of the nodes in the cluster, it becomes the Leader.

- Becoming a leader: The new leader immediately sends a heartbeat message (an empty

AppendEntriesmessage) to all other nodes. This message serves two purposes: to announce its leadership and to prevent new elections. - Losing or timing out: If a candidate neither wins nor loses the election (e.g., a split vote where no candidate gets a majority), it will wait for its election timeout to elapse and then start a new election in the next term.

Handling split votes

What if two nodes become candidates at nearly the same time? You could have a “split vote” where neither candidate achieves a majority.

Raft solves this elegantly using randomized election timeouts. Each node’s election timeout is set to a random duration (e.g., between 150ms and 300ms). This makes it highly unlikely for multiple nodes to time out simultaneously. The first node to time out will usually start an election and win before any other node becomes a candidate.

If a split vote does happen, the candidates that failed to win will simply time out again, start a new election in a new term, and the randomized timeouts make it probable that a single winner will win in the next round.

Log replication: Keeping everyone in sync

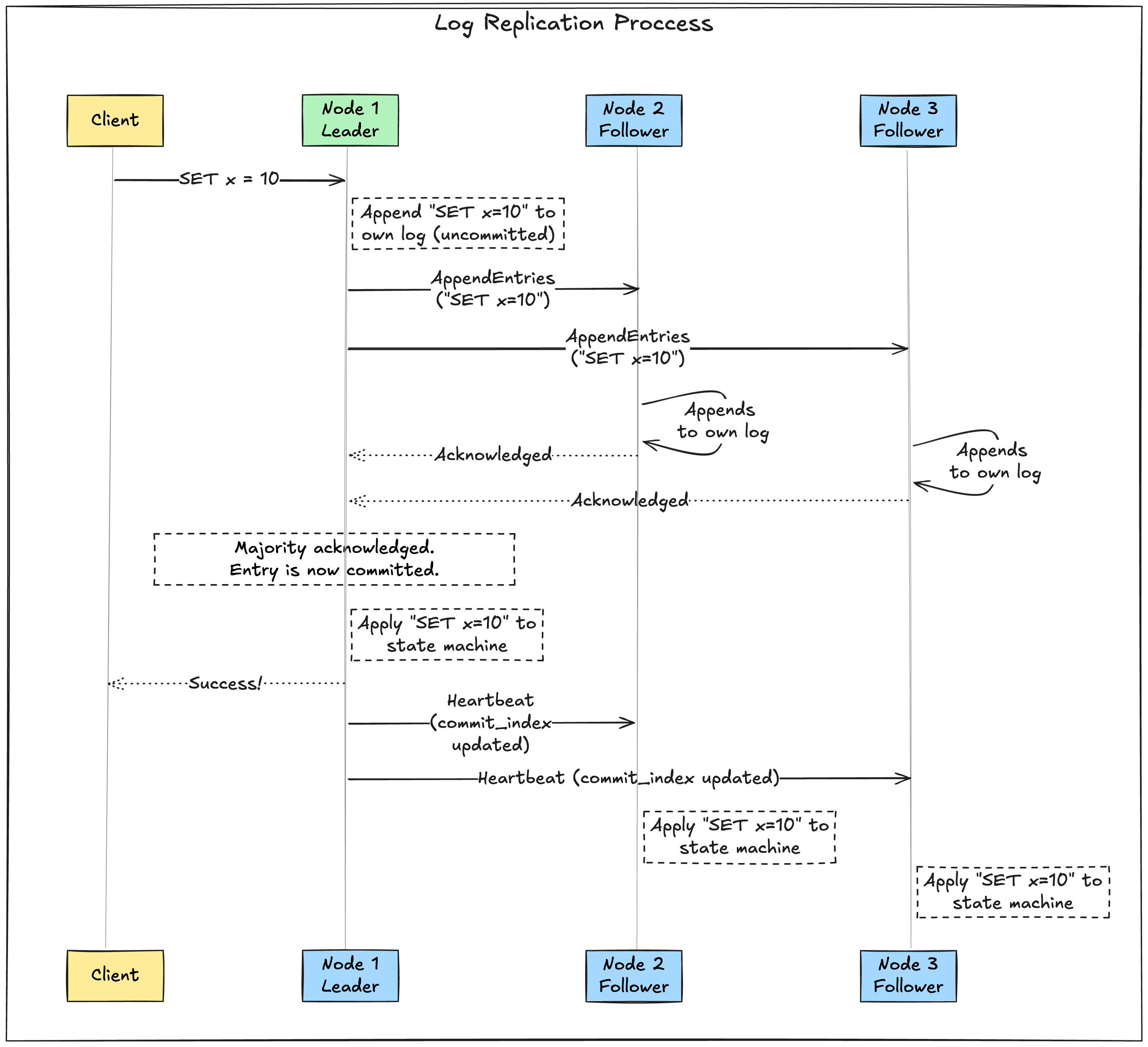

Once a leader is elected, it’s responsible for handling all client requests that modify the system’s state.

Each change is added as an entry to the leader’s log. It’s the leader’s job to ensure that every follower’s log becomes an exact copy of its own. This is Log Replication.

Here’s how that works:

- Client request: A client sends a command (e.g.,

SET x = 10) to the leader. - Append to log: The leader appends the command to its own log as a new entry but does not yet commit it.

- Replicate to followers: The leader sends a

AppendEntriesmessage containing the new entry to all of its followers. - Follower acknowledgement: Each follower receives the message, appends the entry to its own log, and sends an acknowledgement back to the leader.

- Commit the entry: Once the leader receives acknowledgements from a majority of its followers, it knows the entry is safely replicated. It then commits the entry by applying it to its own state machine (e.g., actually setting

xto10). - Notify followers: In subsequent

AppendEntriesmessages (including heartbeats), the leader informs the followers which entries have been committed. Followers then apply those committed entries to their own state machines.

What about network partitions?

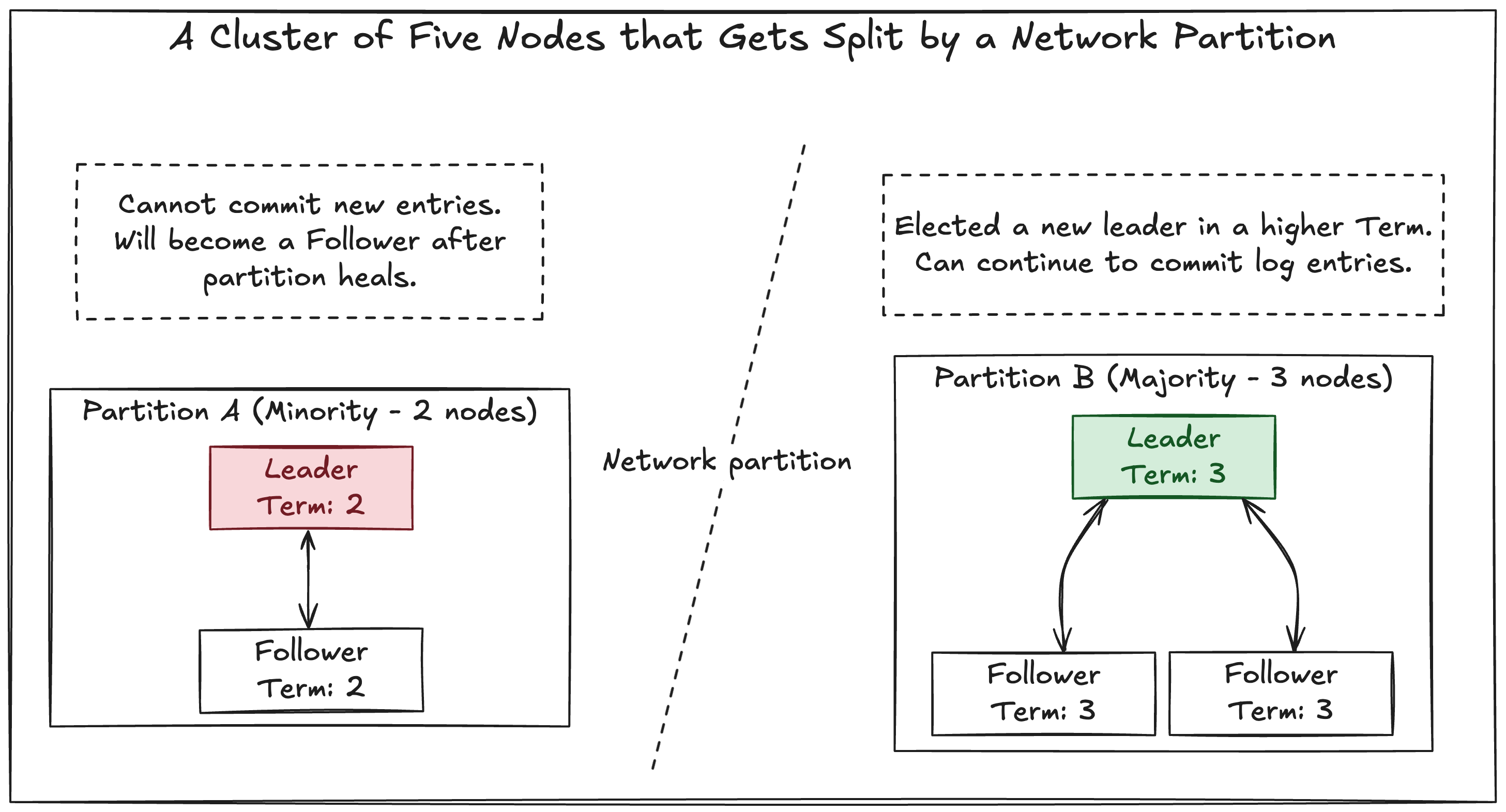

The “majority” rule for both voting and log commitment is the key to Raft’s safety.

Consider a cluster of five nodes that gets split by a network failure into two partitions:

- Partition A: Leader, Follower 1 (2 nodes)

- Partition B: Follower 2, Follower 3, Follower 4 (3 nodes)

The leader in Partition A is now in a minority partition. It cannot receive acknowledgements from a majority (3) of the nodes, so it cannot commit any new log entries.

Meanwhile, in Partition B, the followers will experience an election timeout. Since they form a majority (3 of 5), they can successfully elect a new leader among themselves in a new, higher term. This new leader can accept client requests and commit log entries because it can achieve a majority.

When the network partition heals, the old leader from Partition A will receive a message from the new leader in Partition B. Seeing the higher term number, it will recognize that it is stale, step down to become a follower, and roll back any uncommitted log entries it had, syncing its log with the new leader’s.

This ensures that Raft avoids a split-brain scenario where two leaders make conflicting decisions. Only the partition with a majority of nodes can make progress.

Up next

We’ve covered the core theory behind Raft’s leader election and log replication. In the next post, we’ll start turning these concepts into running Ruby code. Stay tuned!

Comments