Databases are among my favorite systems to learn about. At first glance, they seem like magic boxes that somehow keep our data safe and make it searchable.

But when you peek under the hood, you find a beautifully engineered system that’s all about one thing: managing bytes on disk as efficiently as possible.

In this series, we’ll take a journey into the internals of database systems. How do they store data? How do they find rows so quickly? How do they keep everything consistent when things go wrong?

Before we dive in, let me set some expectations. This series is not about writing better SQL queries or deep dives into data structures theory. Instead, we’ll focus on the practical and low-level stuff of how databases work under the hood. Most of what we’ll cover applies to most relational databases in one way or another.

Note: My experience with relational databases is mostly with PostgreSQL, so that’s where I’ll focus. But honestly, exploring how different databases solve the same problems is one of the best ways to learn.

Why did MySQL/InnoDB choose a clustered index while PostgreSQL uses a heap? What tradeoffs did each make? So whenever it’s relevant, I’ll try to highlight implementation differences between PostgreSQL and InnoDB. I’m learning too, and comparing approaches helps solidify the “why” behind each design decision.

What is a database, really?

At its core, a database is an application that organizes data on disk so that it can be retrieved and modified as efficiently as possible.

Everything else, the query planner, the query optimizer, the transaction manager, sits on top of this foundation. But at the very bottom, it’s all about reading and writing bytes to disk.

So how does a database actually organize those bytes?

The page

You might think that a database works with individual rows when you read or write data. After all, that’s what database queries are all about. But that’s not how it actually works.

A database works with something called a page rather than individual rows, which is a physical collection of bytes on disk that can contain one or more rows.

A page is a fixed-size block of data, typically 8 KB in PostgreSQL.

But why not use individual rows? Because disk I/O has a high fixed cost, databases aim to amortize that cost by reading and writing data in chunks rather than byte-by-byte. Historically, this was especially important for spinning disks (HDDs), where random I/O has high seek latency.

By operating on fixed-size pages, databases minimize the number of physical I/O operations and simplify buffer management, caching, etc.

If each page is 8 KB, then:

- Page 0 starts at byte 0

- Page 1 starts at byte 8,192

- Page 2 starts at byte 16,384

- And so on…

When the database needs Page 45, it calculates the byte offset (45 × 8,192 = 368,640) and reads 8 KB starting from that position.

Ok, but how are pages laid out on disk?

From pages to segment files

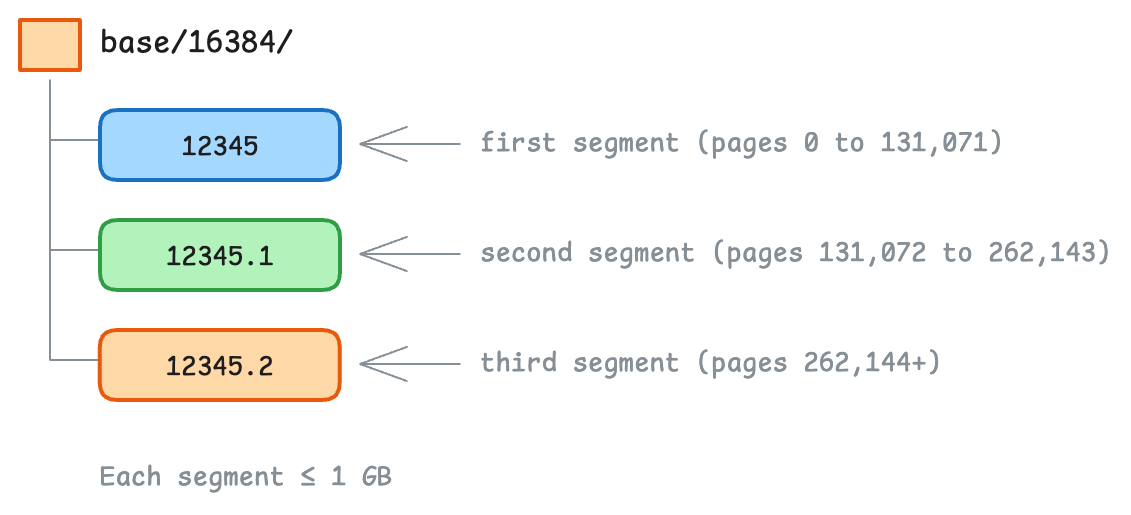

Databases usually split data into segment files with a maximum size (1 GB in PostgreSQL). When one segment fills up, a new one is created, as it doesn’t make sense to do so in one single file that grows forever and becomes a nightmare for backups, caching, file system limits, etc.

In PostgreSQL, each table (relation) is stored as one or more segment files following the following pattern $PGDATA/base/<database_oid>/<relation_oid>:

Given a page number, the database can now calculate which segment file it lives in and the offset within the file by doing:

File number = Floor(PageID / PagesPerFile)

Offset in file = (PageID % PagesPerFile) × PageSize

For example, with 8 KB pages and 1 GB segment files (131,072 pages per file), Page #500000 would be:

File number = Floor(500,000 / 131,072) = 3 (look in file .3)

Offset in file = (500,000 % 131,072) × 8,192 = 500,480 KB

So far, everything is pretty straightforward, and we know how to find the page we need. But how does a table’s data actually get organized across those pages?

How does PostgreSQL organize table data?

In PostgreSQL, table data is stored in a structure called a heap. Despite the name, this has nothing to do with the heap data structure (priority queues). It’s closer to heap memory in C, an unordered collection of data.

A heap is essentially a big pile of pages where rows can be stored anywhere. It’s the simplest way to store data: just throw it in the pile.

When you insert a row into a table, it goes into whatever page (it the table’s heap) has free space. There’s no particular order. This makes inserts fast, but it means the database has to maintain separate indexes to find rows quickly.

A PostgreSQL heap consists of:

- A set of unordered pages

- Rows that can be anywhere across those pages

- Each row is addressed by a TID (Tuple ID)

We will come back to the TID later, but for now, it’s enough to know that it’s a way to address a row in the heap.

How does MySQL/InnoDB do it differently?

MySQL’s InnoDB engine takes a different approach. Instead of a heap, it stores table data directly in a clustered index, a B+ tree ordered by the primary key.

This means:

- Rows are physically stored in primary key order

- The “table” and the “primary key index” are the same structure

- Finding a row by primary key is very fast (just traverse the tree)

Each leaf node in this B+ tree is a page containing actual row data, sorted by primary key.

Whether it is PostgreSQL’s heap or MySQL’s InnoDB clustered index, the data ultimately lives in pages. So what does a page actually look like on the inside?

Rows are messy, and so are pages

Imagine you’re designing the internal layout of a page. You might think: Let’s just pack the rows one after another, like items in an array.

Something like this:

| Row A (50 bytes) | Row B (30 bytes) | Row C (45 bytes) | Free Space ... |

Simple, right? It never hurts to start simple, but this approach has a couple (actually a lot) of problems.

Variable-size rows: Unlike array elements, rows have different sizes. A VARCHAR(1000) column might hold 5 bytes in one row and 500 in another.

You can’t just jump to “row #3” by calculating an offset because you don’t know the size of the row.

Deletions create holes: When you delete Row B, you get a gap! (think about it, it makes sense)

| Row A (50 bytes) | [HOLE - 30 bytes] | Row C (45 bytes) | Free Space... |

Now you’re wasting space. You could compact by sliding Row C left, but that changes its position on the page and therefore its offset.

Indexes need stable references: An index might say, “the row you want is at byte offset 80 on Page 5”.

If you move rows around during compaction, every index pointing to those rows breaks.

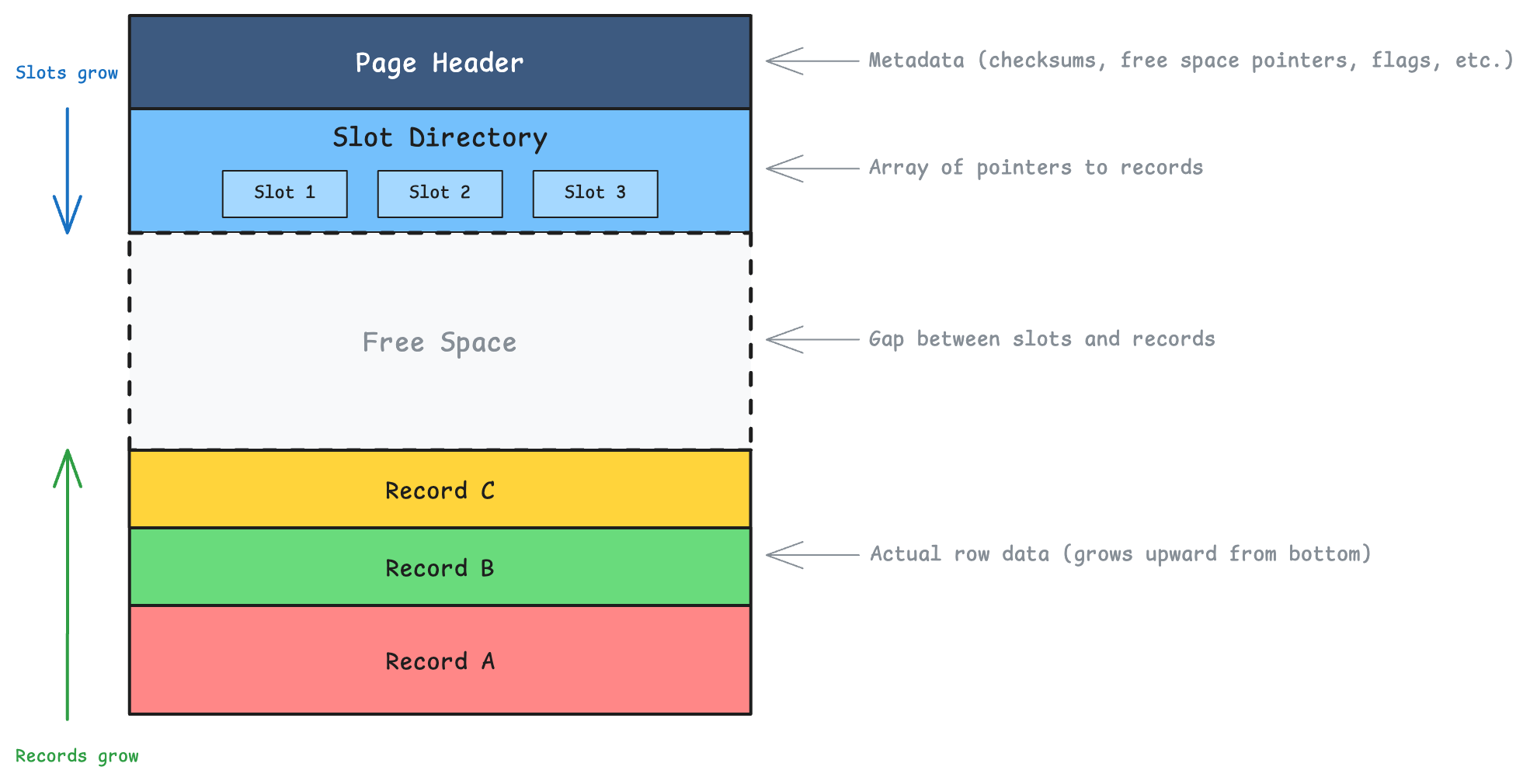

This is exactly what the slotted page structure solves. It’s a way to store rows in a page in a way that allows for efficient lookup and updates.

Slotted pages

Databases (at least those I’ve worked with) solve these problems by adding a layer of indirection in one way or another. In PostgreSQL, it’s the slot directory.

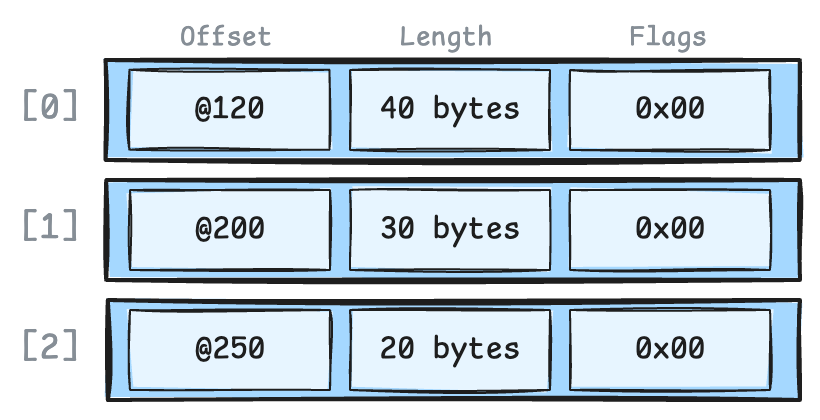

A slot directory is like an array of entries, where each entry points to a record’s location within the page.

Each slot entry contains:

- Offset: Where the record starts (byte position within the page)

- Length: How many bytes the record occupies

- Flags: Status information (is it deleted? redirected?)

You can see where this is going, right? Indexes now don’t point to byte offsets, they point to slot numbers. The slot directory translates slot numbers to actual byte positions.

Why is it brilliant?

Let’s see how the slotted page structure solves the problems we mentioned earlier.

Variable-size rows? No problem. Each slot knows exactly where its record starts and how long it is. Rows can be any size.

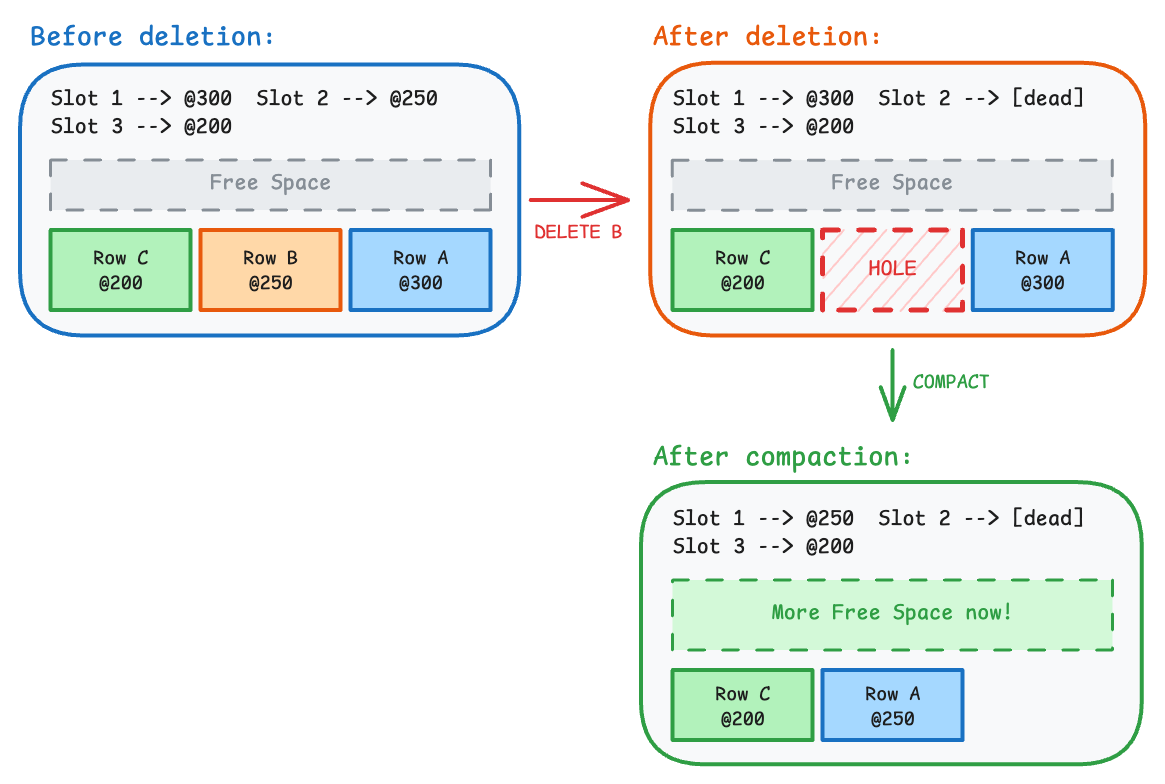

Deletions create holes? Let’s say we delete Row B and compaction happens (note that Row A moved from byte 300 to byte 250, but Slot 1 was updated to point to the new location):

Any index pointing to (Page X, Slot 1) still works perfectly!

Stable index references? This is the magic. Indexes store (Page Number, Slot Number), not byte offsets.

The slot number never changes, even when the underlying row moves around, because the slot directory hides all the physical reorganization.

This combination of

(Page Number, Slot Number)is called a TID (Tuple ID) in PostgreSQL.

This TID-based addressing is elegant, but InnoDB takes a different approach since it stores rows directly in a clustered index and doesn’t need a separate slot directory.

Let’s see how secondary indexes work in both PostgreSQL and InnoDB.

Secondary indexes

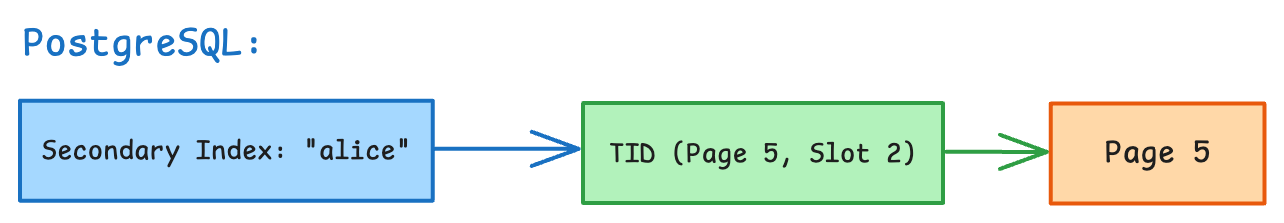

As we mentioned earlier, PostgreSQL and MySQL/InnoDB take very different approaches to organizing table data, and this is reflected in how they handle secondary indexes.

Let’s say we have a secondary index on the username column of our users table, and we do the following query:

SELECT id, username FROM users WHERE username = 'alice';

PostgreSQL: Secondary indexes store the TID directly.

When you look up “alice”, the index gives you the exact physical location. Fast! But if that row moves to a different page (during VACUUM or an update that changes the row size), every index on that table must be updated.

MySQL/InnoDB: Secondary indexes store the primary key value.

Looking up “alice” requires two steps: first, find the primary key in the secondary index, then look up the row in the clustered index. Slightly slower for reads, but if a row moves to a different page, secondary indexes don’t need updating.

But wait, does PostgreSQL really update every index on every row change? That sounds expensive, right?

What happens when you update a row?

Both PostgreSQL and InnoDB use MVCC (Multi-Version Concurrency Control), which means they never modify a row in place. Instead, they create a new version of the row and keep the old one around for transactions that might still need it.

This raises an important question: if every update creates a new row version, do all the indexes need to be updated too?

The naive approach (and why it hurts)

Consider a table with 5 indexes. Without any optimization, every UPDATE would:

- Create a new tuple (row version)

- Update all 5 indexes to point to the new location

This is expensive because:

- Index writes are random I/O (jumping around the disk)

- Index bloat grows quickly

- Write amplification is high (1 logical write becomes 6 physical writes)

For tables with many indexes and frequent updates, this becomes a real bottleneck.

PostgreSQL’s clever trick: HOT updates

PostgreSQL asked a simple question: What if the UPDATE doesn’t touch any indexed columns?

Think about it. If you’re updating a status column from 'pending' to 'complete' and status isn’t indexed, why should the indexes care? The indexed values haven’t changed.

This insight led to HOT (Heap-Only Tuple) updates.

A HOT update creates the new row version on the same heap page and links it from the old slot, avoiding any index updates entirely.

For a HOT update to work, two conditions must be met:

- No indexed columns are modified

- The new row version fits on the same page (because if it didn’t, we would have to do a regular update to update the page ID for that TID in the index)

If either condition fails, PostgreSQL falls back to a normal update (I’m sure there are some other optimizations for this, but let’s keep it simple for now).

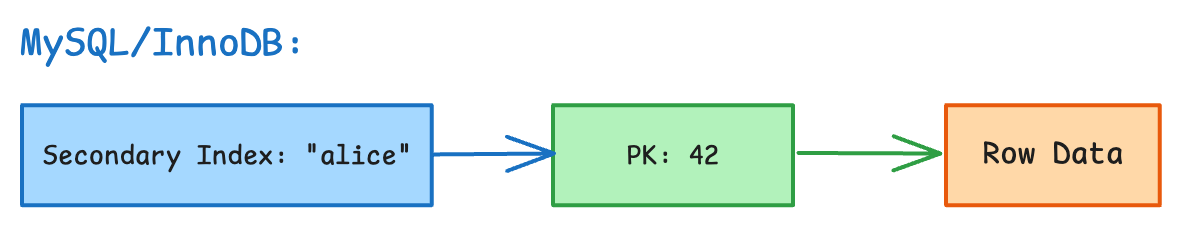

HOT in action

Say we have an orders table with an index on id, and we run:

UPDATE orders SET status = 'closed' WHERE id = 10;

Since status isn’t indexed, PostgreSQL can do a HOT update:

The magic here:

- The old tuple is marked dead

- A new tuple is written to the same page (Slot 3)

- Slot 1 becomes a redirect pointer to Slot 3

- The index entry stays the same

When a query follows the index to (Page 42, Slot 1), it finds the redirect and follows it to Slot 3. No index update needed!

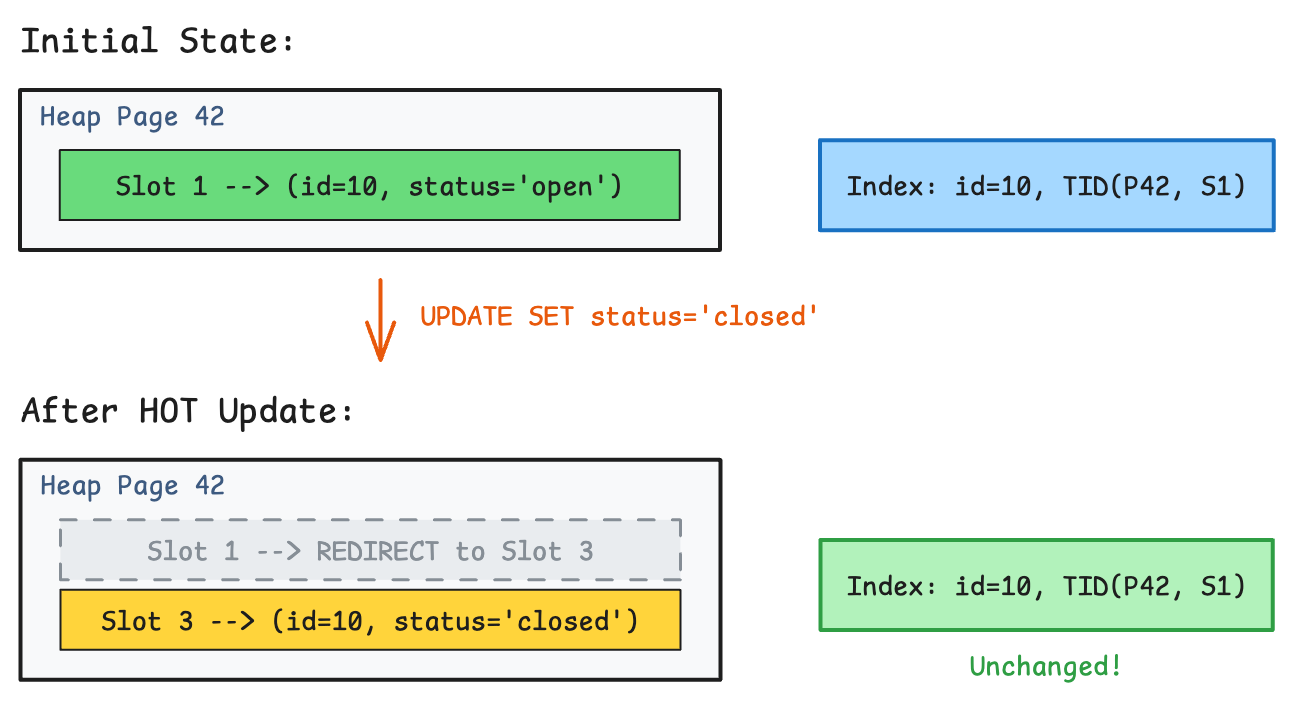

HOT chains

If we update the same row again (still not touching indexed columns), the chain grows:

Each update adds a new version to the chain. The index still points to Slot 1, and readers follow the chain to find the currently visible version.

But remember: HOT chains never cross page boundaries. If the new version doesn’t fit on the same page, PostgreSQL has to do a regular update and touch the indexes.

VACUUM and HOT chains

Over time, old tuple versions become invisible to all transactions. That’s when VACUUM steps in:

- Removes dead tuple versions

- Collapses HOT chains

- Reclaims the redirect slots

The chain is gone, and Slot 1 points directly to the current version.

Whew, that was a lot! But fun, isn’t it?

What’s next?

We’ve covered a lot of ground: how databases organize data into pages, how the slotted page structure enables stable yet flexible storage of row data, and how PostgreSQL’s HOT optimization helps reduce write amplification.

But there’s a big assumption we’ve been making throughout this post: that pages are just sitting on disk waiting to be read or written to. In reality, constantly reading and writing to disk would be painfully slow.

So how do databases avoid this?

In the next blog post of this series, we’ll explore the Buffer Pool, the in-memory cache that sits between your queries and the disk.

Stay tuned!

Comments